Introduction¶

"If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?"

Most likely, you are reading this article because you are curious and assume it contains some sort of interesting knowledge, but what does it even mean to know something? Usually when we think of "knowledge" we think of truth, fact or "information." An interesting place to start defining knowledge is the observation that if you knew the entire content of this article, ahead of time, then you woudn't gain any new knowledge by reading it again. In other words, if I tell you to read a book, but you already know all of the events in the plot, then the "information" you gain by reading it again would be virtually zero. How much knnowledge you gain is proportional to how surprised you are by what you observe.

Let's extend this idea further: if a tree falls in a forest, how do you know that this event actually happened? \ One way to answer this question is to look at the tree as an "entity" that communicates information to you when it falls.\ If you're standing right next to the tree, then you know it fell when you physically see it falling... the *knowledge* is communicated by all the light scattering off and into your eyes, the same way the knowledge contained in

The Observer Effect:¶

The falling tree creates various physical signals: sound waves, vibrations in the ground, visual movement, displaced air molecules, etc. Each of these signals carries potential information about the event. For this information to be "known," it must be received and processed by another entity. If no conscious observer is present, the physical phenomena still occur - sound waves propagate through the air, disturbing molecules. However, the information transfer that constitutes knowledge acquisition doesn't complete its journey. The signals exist, but they aren't percieved and decoded into meaningful information by a receiver. This brings us to an important distinction between physical phenomena and knowledge. Physical phenomena exist independently of observation, but knowledge necessarily involves a perceiving entity.

When we ask if a falling tree "makes a sound," we're actually asking two distinct questions:

- Do compression waves propagate through the air when a tree falls? (A physics question)

- Is the information contained in those waves received, processed, and converted into knowledge? (An epistemological question)

The answer to the first is clearly "yes" - the physical processes occur regardless of observation. The answer to the second depends entirely on the presence of a receiver capable of transforming those signals into knowledge. This distinction highlights the fundamental nature of information: it represents the measurable transfer of knowledge from one entity to another.

A basic idea in communication theory is that information can be treated very much like a physical quantity such as mass or energyClaude Shannon

To formalize this idea, we define information as a measure of knowledge transfer from an originating source to a recipient that previously lacked that knowledge. This transfer occurs when a signal is not only generated but also received and interpreted.

$$ \newcommand{\I}{\mathit{I}} \I $$

Defining information $\I(*)$:¶

Let us define the information content of an event using the function $\I$, which assigns a value based on the probability of an event occurring:

$\I(P(X = x)) = f(P(X=x))$, for some function $f(*)$

We expect $\I$ to have the following properties:

$\I : [0,1] \rightarrow [0, \infty)$

- An event thats 100% probable, yields no new information. If we're completely certain of a specific outcome of some event,

then we already hold that information and thus measuring the information content of this event gives us a value of 0. - The less probable an outcome of an event, the more surprising it is and the more information it yields. An outcome with 0% probability, has an information measure that approaches infinity, as we just observed something we believe to be impossible.

- Information is always positive. If you think about it, The idea of "negative information" makes no sense. You can't unsurprise someone, just like there is no piece of information that I can tell you that will destroy some piece of information that you already hold.

- Information is continuous, We would like I’s domain to be continuous in the interval [0,1].

That is, a small change in the probability of an event should lead to a corresponding small change in the surprise that we experience.

$\I(A \cap B) = \I(A) + \I(B)$

- Information is additive: If $A$ and $B$ are independent events, then the information gained by observing both should just be information of A + information of B

Finding $f(*)$:¶

Start with the definition of independent events:

$P(A \cap B) = P(A) \times P(B)$

This means:

$\I(A \cap B) = f(P(A) \times P(B)) = \I(P(A)) + \I(P(B))$

Analyzing Cauchy's functional equations show us that for:

$f(x \times y) = f(x) + f(y)$

the only function $f(*)$ that satisfies all of the above properties, is:

$f(x) = Klog(x)$

The only K that satisfies all of our properties defined above is K=-1

Self-Information¶

$\I(p) = -log(p)= \log(\frac{1}{p})$

From our derivation, we can see that $−log(p)$ satisfies all our desired properties for quantifying information.

This is known as Shannon information or self-information, named after Claude Shannon who formalized Information Theory in the 1940s.

Here's what $\I(p) $ looks like graphically:

But why does $\I(p)$ change with respect to the base? What does "information content" have to do with which logarhitm we choose?

Turns out, just like I can measure length in meters or feet, the base of the logarithm in our self-information function represents the units in which we measure information.

Different bases correspond to different measurement systems, most common are:

Base 2 (log₂): Measures information in bits (binary digits), which is useful in digital communication and computing.

Base e (ln, natural log): Measures information in nats, often used in statistical mechanics and probability theory.

Base 10 (log₁₀): Measures information in Hartleys, which is useful in certain engineering applications.

Reality is an entity communicating uncertain events¶

Another way to interpret "information" is as a measure of surprise rather than amount of knowledge. Think about it, just like the examples before, If you read a certain book that you have completely memorized, then the information you gained is zero. However, if you insisted on reading the book and in the middle of it you surprisingly encounter a brand new chapter that you haven't seen before, then suddenly you have gained a lot of new information.

This hints at a deeper truth within about information: When we view the entire universe as an entity, we cannot possibly know how complete the information communicated to us is. To put it bluntly, because we cannot with a 100% certainty predict the future, there is always new events to be observed and new physics to be discovered. When we talk events in the real world, we have to assume the information given to us by the universe is random. Thus we often wanna measure how uncertain we are about the information content

Flipping Coins:¶

Let's say we made a bet: I flip a coin, and ask you to predict the answer ahead of time. If your prediction is right, I double your investment

If you predict $Tails$, how certain would you be of your answer? In some sense, placing a bet is akin to saying that you're certain of a particular outcome.

But we know that the probability of getting $Tails$ is $\frac{1}{2}$... a 50% chance that you're right.

Now lets say, before taking your money, I flipped the coin 8 times and showed you the outcomes:

$X = \set{H,H,T,H,T,H,H,H}$

Would you still pick $Tails$? Intuitively, the answer is no: out of the 8 flips we only get 2 that are Tails, suggesting that the coin is heavily biased in favor of Heads.

But why are we so inclined to believe the coin is biased only after 8 flips? After all, its entirely possible that we just got a very lucky set of observations.

This is where measuring information starts making intuitive sense.

Heads: 0

Probability: 0%

Tails: 0

Probability: 0%

Sequence History

| Flip | Result | H/T Distribution |

|---|

Let's start with our prior beliefs: since we're betting, we think the coin always comes out $Tails$. The first observed $Heads$ communicated to us $I(0) = \infty $ information, since us our belief didn't think this outcome was even possible. So, we split the total probability in two and aassume the coin is fair, giving the two outcomes equal probabilities $P(x_i = Tails) = P(x_i = Heads) = \frac{1}{2}$. Now, we can say that the first observation communicated $\I(\frac{1}{2}) = 1$ bit of information. After 8 flips, I would have communicated $8\times\I(\frac{1}{2}) = 8 \times -\log_2 (\frac{1}{2}) = 8 $ bits of information.

But, in the 8 flips we predominantly observe $Heads$, so let's assume that the 8 flips indicate the true distribution $P(x_i=Tails) = \frac{2}{8}$. This means that the information conveyed to us is actually $8*\I(p_{tails}) = 8 * -\log(\frac{1}{3}) \approx 8*1.585 = 12.68$ bits for the 8 flips... substantially higher than if the coin was fair, which makes sense since we're surprised that the two outcomes aren't equally likely. This highlights another interesting property of information: How much information you recieve depends on your prior beliefs about the event.

We can also look at the outcome of the 8 coin flips as a single event. The following table shows $\I(p)$ for all 8 possible coin flips, where $p$ is the observed probability distribution of getting the most common outcome:

For instance:

$\I(X = "HHTHTHHH") = \I(P(x_{i+1}=Heads)) = -log_2\frac{6}{8}= 0.4$ bits:

There are $2^8 = 256$ possible outcomes for the 8 flips. If we look at the sequence "HHHHHHH", we can see that it has the self-information value of 0 because if we assume that this is the true distribution for the coin,\i.e $P(x_{i+1}=Heads) = 1$, which is the same as assuming that the coin always flips to $heads$, then, observing another $heads$ for the 9th coin flip would be the least "surprising" outcome. In this framing, the 8 coin flips are telling us at most 1 bit of information: is the coin fair or not?

If we're betting on a flip of a coin, then we want to know if theres a clear pattern to its outcomes based on our previous observations. If there's an equal amount of $Heads$ and $Tails$, then we don't know what to bet on, but if all the outcomes are $heads$, then we might want to bet on $heads$. Another way to frame this is to ask: how disordered is the set of observations? In other words, how surprising is this sequence, if we assume all outcomes are equally likely?

The Guessing Game¶

Suppose I'm thinking of a certain letter in the english alphabet. If you guess it right within 6 tries, I will double any amount of money you bet... should you play this game? On the surface, it might seem like 6 guesses is not enough to make the game worth playing, so to sweeten the deal further, every time you make a guess, I will tell you if the letter I'm thinking of comes before or after your guess. This might still seem like a losing game, but suprisingly, this game is heavily rigged in yourr favor. To see why you should play for a few runs,and see that the averaged number of guesses converges to the value of 5.

Every time you play the game, you can expect it to only take 5 guesses to figure out which letter I'm thinking of, and since thats less than the allowed number of guesses, the odds of winning are in your favor. Ok, but how is it possible for it to take only 5 guesses to pick 1 letter out of 26 possible choices? The answer reveals one of the most interesting properties of information: since its a measure of surprise, it's also inherently a measure of uncertainty reduction. Think about what's happening when you play the game. Every time you make a guess, you reduce your uncertainty of where the letter is located in the sequence by half. And if you divide 26 by half over and over, it would take only 5 halvings until you arrive at a value of less than 1, implying close to complete certainty over where the chosen letter is. If you ever took an algorhitms course, you might recognize this structure as a special case of a binary search tree

Suppose now we play the game but with the the set of all possible chinese characters, can we extend this idea to know how many guesses it would take without having to play the game?

Measuring Disorder¶

Another way to say disorder is "entropy," Lets define a measure of entropy as a function $H$.

$H(X) = f(X)$, for some set $X = \set{x_1, x_2, x_3... x_n}$ and some function $f(*)$

We expect $H$ to have the following properties:

$H(X) : X \rightarrow [0, 1]$

- A set of observations, where each outcome is different and unique is completely disordered. If we see no discernable pattern to the outcomes, then we say that the set is random and the entropy measures the value of 1.

- A set of observations with only one type of outcome, is completely ordered If we only see a clear pattern in the set, then it is ordered and the measure of entropy gives the value of 0.

- Disorder is always positive. Just like before, The idea of "negative disorder" doesn't make sense, in the context of knowledge. If you look at a set of coin flips, there is no "dis-disorder" that you can measure.

- Disorder is continuous, Because disorder depends on the information content of the input set, we would like I’s domain to also be continuous in the interval [0,1].

That is, a small change in the information leads to a corresponding small change in the disorder that we measure.

$H(A \cap B) = H(A) + H(B)$

- Disorder is additive: If $A$ and $B$ are independent events, then the measured entropy of both sets of observations would just be entropy of A + entropy of B

If you compare, the properties of $H$, they're pretty much identical to the properties of $I$, that's because entropy is really just taking a set of information measures, i.e $X = \set{I(x_1), I(x_2)... I(x_n)}$

and transforming them to the 0 to 1 domain, where

$H(X) = 0$, means $I(x_1) = I(x_2)... = I(x_n)$

and

$H(X) = 1$, means $I(x_1) \neq I(x_2)... \neq I(x_n)$

This means that $f(*)$ is really just the extected value operator, meaning H(X) is really just the average of X.

This highlights a fundamental principle: information exists as a potential, but knowledge requires communication. Without an observer, the event still happens, but it does not become known. This reinforces the idea that reality consists of events communicated between entities—and without a receiver, the information does not transition into knowledge. Entropy, in some sense, is the measure of potential information we think we will recieve by further observing a system.

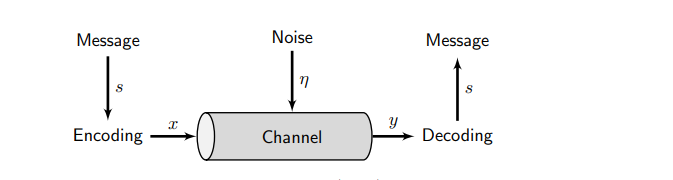

Encoding¶

The Source Coding Theorem leads us to interpret the base of the logarithm used in the definition of I as the number of symbols in the alphabet that Person A is using to construct their messages. Said differently, the base of the logarithm in the definition for I can be understood as the size of a hypothetical alphabet that we are using to communicate the result of a surprising event.

Conclusion¶

Information theory provides a mathematical framework for understanding knowledge as a quantifiable transfer between entities. It suggests that reality itself might be conceived as a network of information exchanges between entities, with knowledge emerging from these exchanges. When we ask whether a falling tree makes a sound when no one is around to hear it, we're really asking about the nature of information itself—whether it exists independently of being received and interpreted. The mathematical formalism of information theory suggests that while the physical basis for information may exist independently, information as a meaningful concept requires both transmission and reception.